Fusion robots advancing into UK space industry

Above:

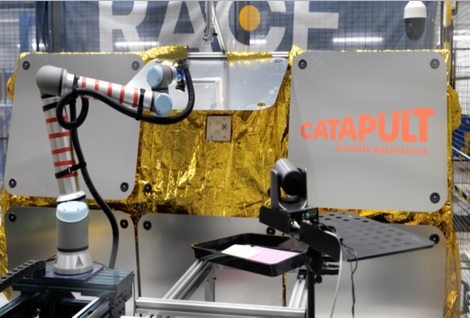

Fusion robots at work in UK space industry, UKAEA, Culham.

Courtesy UK Atomic Energy Authority

Culham and Harwell, Oxfordshire - UK Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) and the Satellite Applications Catapult have partnered to demonstrate how advanced remote handling and robotics technology developed for fusion energy research can be used to provide maintenance for in-orbit satellites.

The technology has been developed and tested at UKAEA’s Remote Applications in Challenging Environments (RACE) robotics centre in Culham, Oxfordshire.

The demonstration adds to evidence that the potential economic spill over of fusion research reaches far beyond the sector itself and even as far as the servicing of spacecraft in orbit.

Fusion is the process that powers the sun and stars. The energy created promises to be a safe, low carbon and sustainable part of the world’s future energy supply.

Dr Indira Nagesh, Principal Engineer of UKAEA, said of the network spillover: “The rewards for recreating the ultimate fusion energy source here on Earth are enormous, with the potential for near limitless power for generations to come. Right now, we’re proving that our technology has lots more immediate benefits in adjacent sectors.

“Identifying technical challenges and solving them for in-orbit servicing and repair is exciting. It will greatly help to improve the longevity of spacecraft and reduce space litter.”

Jeremy Hadall, Robotics Development Lead at the Catapult, said: “Improving our ability to perform close-proximity operations in orbit with advanced robotics, will unlock a range of commercial opportunities in space including debris removal, spacecraft servicing, and even the manufacture of large structures in orbit. This trial moves the space industry one step closer to realising these exciting possibilities.”

Currently, around 6,000 satellites are in orbit around the Earth, but only 40% are operational. This space debris poses a danger to all spacecraft which have to perform thousands of avoidance manoeuvres each year to prevent collisions. Servicing and maintenance can extend operational lifetimes and the same technologies can be used to support active debris removal missions.

Hadall continued: “While the space industry has assembled structures and serviced them in the past, it has been extremely costly and required national agencies to lead. However, there is a significant commercial requirement to remove these barriers using robotics as we expand our reach beyond Earth.”

A replica section of a typical spacecraft provided by Satellite Applications Catapult was assembled at RACE.

Demonstrations were carried out in the Automated Inspection and Maintenance Test Unit (AIM-TU), a highly modular robot cell for research and development containing two UR10e (Universal Robotics) robots with 1.3 metre reach.

A ‘digital twin’ of the operation using specialist software was also completed to show how operators can take over the manual command of the operation, if required, and train the system to carry out new missions.

While the automation is not space-qualified, engineers have demonstrated how such processes can potentially be replicated in space by understanding technical challenges in implementing remote handling capability.

“The demonstrations have shown how fusion energy technologies can support faster and safer operations,” added Mr Hadall.

“We’re pleased to be working with UKAEA on this collaboration and envisage the relationship to continue as both organisations look to spur innovation by addressing common challenges,” he concluded.

Since its opening at Culham, Oxford, in 2016, UKAEA’s RACE facility has conducted research and development in the use of robotics to protect people in challenging environments.